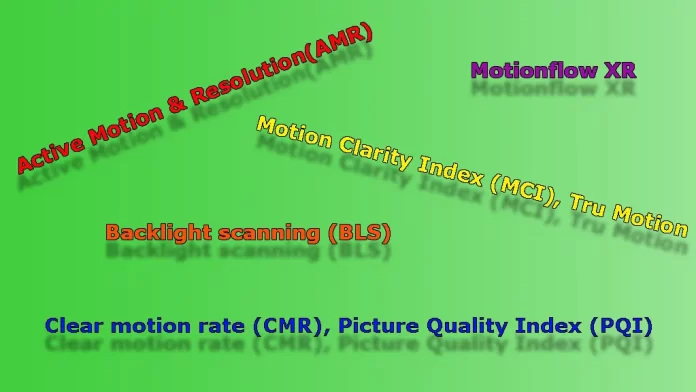

In the early years of digital television, manufacturers began heavily promoting their displays with bold claims about how smoothly they could render motion. To support these claims, each brand introduced its own version of a “dynamic scene index” — a proprietary metric supposedly measuring the TV’s ability to handle fast-moving scenes.

Toshiba had Active Motion & Resolution, Samsung used Clear Motion Rate and later Picture Quality Index, LG rolled out the Motion Clarity Index before switching to TruMotion, and Sony introduced Motionflow XR. Panasonic marketed Backlight Scanning, Philips talked about Perfect Motion Rate, and Thomson used Clear Motion Index. For plasma TVs, Samsung employed Subfield Motion. Despite the variety of names, these technologies essentially aimed to convince consumers that their TV delivered a smoother, clearer image during fast-moving scenes.

However, the numbers tied to these indexes quickly became exaggerated — some TVs were advertised with motion rates of 1000, 2000, or even 10,000 Hz. These figures weren’t tied to real refresh rates or measurable performance. At first, manufacturers implied that these values were in Hertz, but after facing legal action and growing consumer skepticism, they backed away from this claim. Eventually, these inflated numbers persisted without any technical explanation at all.

The peak of this marketing trend came around 2013. Over time, brands quietly phased out their original indexes and replaced them with new names. But the essence remained the same — more about marketing than meaningful technical improvement.

How Motion Enhancement Technologies Actually Work on Modern TVs

TV manufacturers once claimed that their displays could improve dynamic scenes by generating intermediate frames between the original ones, thereby increasing the apparent frame rate and creating a smoother image. In theory, this would make motion appear more fluid and natural.

In practice, however, consumer-grade TVs lacked the processing power and memory to generate fully new frames in real-time. Instead, they used simpler methods — duplicating frames or inserting black frames between existing ones. This creates a visual illusion of smoother motion, especially when content is filmed at 24 or 30 frames per second but displayed on screens capable of 60 or even 120 Hz.

For example, when a TV receives a 30 fps signal but supports 60 Hz playback, it can simply repeat each frame to fill in the gaps. More advanced TVs insert black frames between regular ones to increase clarity and reduce motion blur. On 120 Hz displays, the effect is further enhanced. These techniques do help smooth motion to some degree, but they are far from the true frame generation that was originally suggested.

It’s also important to note that if the content already has a high frame rate — such as 60 fps or higher — these technologies become redundant and are usually disabled automatically.

Why Motion Clarity Indexes Disappeared from Screens and Ads

One of the major downsides of motion enhancement is the so-called “soap opera effect.” This occurs when the image becomes too smooth, stripping away the cinematic feel that viewers expect from movies and high-end shows. Instead of looking natural, the content appears hyper-realistic — as if it were shot on a cheap video camera. Many viewers find this effect jarring and unpleasant, prompting them to disable motion smoothing features entirely.

As more content is now created with higher native frame rates, the need for artificial motion enhancement has diminished. Alongside that shift, the inflated motion indexes have also faded away. In the United States, manufacturers largely abandoned these indexes by 2017. In Europe, they lingered a bit longer, but by 2021, they had mostly disappeared.

Today, manufacturers focus less on flashy marketing numbers and more on delivering real performance. The era of motion clarity indexes — once a staple of every spec sheet and TV commercial — is largely over, remembered as a phase when marketing raced ahead of the actual technology.